The Wounde d Prophet by Michael Andrew Ford paints an honest and sympathetic picture, examining all areas of Nouwen’s life, including his family upbringing, his vocation as a priest, his outstanding gifts as a writer and speaker, his friendships, his sexuality and his deep restlessness.

d Prophet by Michael Andrew Ford paints an honest and sympathetic picture, examining all areas of Nouwen’s life, including his family upbringing, his vocation as a priest, his outstanding gifts as a writer and speaker, his friendships, his sexuality and his deep restlessness.

REVIEW

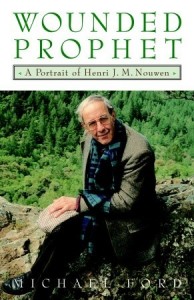

The Wounded Prophet was the first full portrait of Henri Nouwen to emerge after his untimely death in 1996 and paints an honest and sympathetic picture, examining all areas of Nouwen’s life, including his family upbringing, his vocation as a priest, his outstanding gifts as a writer and speaker, his friendships, his sexuality and his deep restlessness. In this new edition, 10 years later, Michael Andrew Ford reflects further on the process of writing the book and the reactions to its publication, on Nouwen’s enduring appeal and his legacy as a great spiritual writer. It presents an insightful profile of a man whose spiritually profound books emerged from his own wounded and searching soul. It remains essential reading for all those who have been touched by Nouwen’s writing.

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Henri Nouwen’s Life – a Summary

The Construction of a Memory

Prologue

Encounter

I. Heart

1. Mystical Path

2. Deep Wells

3. High Wires

4. The Dance

5. Backstage

6. Wounded Healer

7. Visions of Peace and Justice

8. The Gift of Friendship

II Mind

9. A Priest is Born

10. Holy Ground

11. A Meeting of Minds 12. Connections

13. The Art of the Teacher 14. Silent Cloisters

15. The Mission

16. Brainstorms

17. Icons

III Body

18. Slowly Through the Forest 19. Rite of Passage

20. Inner Darkness

21. The Father

22. The Way Home

23. New Directions

24. The Mystery of Love

Epilogue

Blessing

Notes

Bibliography

Index

242pp, Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd., 1995. To purchase this book online, go to www.darton-longman-todd.co.uk.

CHAPTER 0NE

MYSTICAL PATH

Henri Nouwen was a priest whose identity was rooted in what he always referred to as ‘God’s first love’. Praying before the Blessed Sacrament every day, sometimes lying prostrate, he believed in theology’s original meaning – union with God in prayer – and nothing would keep him from this encounter. Even if he had been awake all night, as he often was, compulsively telephoning friends around the world, offering as well as receiving support, he would still get up at 6 a.m. to say the divine office when staying with his family in Holland, his brother would hear him pacing around the attic bedroom at dawn, following the Liturgy of the Hours before going off to Mass in a local church. But wherever his reveille with the Lord, it was rarely without its own chaotic chorus.

His primary need for prayer meant he was completely oblivious to more mundane things. He would dash to the bathroom wherever he was staying and shower without closing the curtain, soaking the place in water. Then, without looking in the mirror, he would shave as quickly as possible, so he could get downstairs and be with God. As a result, he often ended up with a one inch patch of old whiskers on his neck and fresh soap in his ear.

Nouwen was, in fact, a sensuous man whose massive hands, alive with nerve endings, were drawn to the smooth contours of aromatic soap as they were to the shiny grey rosary beads which he always carried round in his pocket. During prayer he could become transfixed by the size and weight by the size and weight of the stones as well as by the distinctive sounds they made. In his room, often aglow with candles and icons, he would rub the beads over the surface of his hands as if they were Braille and, with the same sensory touch when celebrating Mass, he would sometimes lift the glass chalice with one hand and caress its curvature with the other. Although rarely seen in his Roman collar, he loved to wear long, coarsely woven stoles, made of soft pastel fabrics. As he walked around the big weighty tassels hit his legs and back reminding him of his responsibility to the priesthood into which he had been ordained in Utrecht Cathedral in 1957 and to whose archdiocese he was ultimately answerable.

Contemplation was at the heart of Henri Nouwen’s life. It was a discipline of dwelling in the presence of God. Through fidelity in prayer, he could awaken himself to the God within him and let God enter into his heartbeat and his breathing, into his thoughts and emotions, into his hearing, seeing, touching and tasting. Nouwen was convinced that Christian leaders need to reclaim the mystical so that every word they speak, each suggestion they make and every strategy they develop, will emerge from a heart which knows God intimately. He wrote:

I have the impression that many of the debates within the Church around such issues as the papacy, the ordination of women, the marriage of priests, homosexuality, birth control, abortion and euthanasia take place on a primarily moral level. On that level, different parties battle about right or wrong. But that battle is often removed from the experience of God’s first love which lies at the base of all human relationships. Words like right-wing, reactionary, conservative, liberal, and left-wing are used to describe people’s opinions, and many discussions then seem more like political battles for power than spiritual searches for the truth. (1)

Through acts of devotion and adoration Christian ministers had to learn to keep listening to the divine voice of love and find within it the wisdom and courage to address contemporary issues. Only then would it be possible for them to remain flexible without being relativistic, convinced without being rigid, willing to confront without being offensive, gentle and forgiving without being soft, true witnesses without being manipulators.

Such thinking underpinned the whole of Nouwen’s theology and was never more evident than in his relationships with other people, especially in a sacramental context. Every Mass at the L’Arche Daybreak community in Toronto, where he spent the last ten years of his life, was an artistic event. He would involve children and adults, handicapped and able-bodied, asking them to act out what he was saying. No one was excluded and it had to be alive. ‘There was a kind of living artistic sensibility in Henri’s way of being, in his way of structuring worship and in his way of celebrating’, said his friend, Carolyn WhitneyBrown, herself an artist. ‘L’Arche celebrates diversity and eccentricity, and that was one of Henri’s fundamental beauties: his absolute delight in eccentricity, peculiarities and the uniqueness of people. He had very good eyes to see that, and for me that was a profoundly artistic sensibility’.

But for Nouwen the practice of prayer was never easy. While many readers might imagine their favourite author to be a serene guru-figure, praying in a contemplative posture, they could not be more mistaken: he could rarely sit still for long. When he was in prayer, he fidgeted, coughed and moved but seemed to have no awareness he was doing it. His apparently restless and distracted prayer nurtured him. While his body was twitching, his spirit could be deeply present to God.

It was all the more surprising, then, that a man of such distracted temperament should have decided to accept an invitation to join the still world of the Quakers. The writer Parker Palmer has never forgotten the first time Nouwen turned up at a retreat centre where the traditional gathering in silence was practised for 45 minutes every morning:

I was conscous of being in the company of a world-class contemplative and I was expecting to have an extraordinary experience sitting next to him during worship. But as we sat in this plain, unadorned room and settled into the silence, I realised that the bench was jiggling. I opened my eyes, glanced to my left and saw Henri’s leg working furiously. He was anxiously trying to settle but without much success. As time went on, the fidgeting got worse. I opened my eyes again only to find him checking his watch to see what time it was.

This incident introduced Parker Palmer to a person of paradox who indeed had a profoundly contemplative heart but who needed to be constantly on the move, a man filled with immense energies which were difficult to harness. But did such tensions collaborate to form a certain kind of genius? As a spiritual author himself, Palmer believes that Nouwen’s books were deeply engrossing and engaging precisely because they came out of this ongoing wrestling match between the paradoxes in his own life. He practised what he preached – and he preached the struggles, sometimes the anguish, sometimes the joy, which he himself was living.

Wherever he was in the world, Nouwen celebrated Mass every day, in churches, chapels or hotel suites. If he was staying with friends, he would ask them to join him for a celebration around the dining-room table, usually at 5 p.m. He welcomed anyone, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, to receive the sacrament. He was sufficiently secure in his belief that the Eucharist was a gift to humanity to be able to sit loosely to the official Roman position that only Catholics in full communion with the Church should be allowed to receive. Nouwen was even prepared to give the sacrament to non-baptised members of his own family – although, if they received regularly from him, he would suggest that they might like to think about joining the Church officially; but he would never insist.

In the setting of L’Arche, where community members came from many traditions, Henri Nouwen was sensitive to the difficulties surrounding intercommunion. But in the context of small community gatherings, he was pastorally concerned for non-Catholics, who always found him welcoming if they wished to receive Holy Communion: people and their relationship with God mattered much more than strict adherence to ecclesiastical law. What was harder for him was getting to Mass on time. The congregation at Daybreak grew accustomed to their pastor rushing in at the eleventh hour – the art of genuflecting on the run became a liturgical gesture in itself – yet the impact of his eucharistic services was always profound and was remembered long afterwards.

His Masses were never divorced from the immediate needs and concerns of the particular community he was serving and were celebrated with reverence, passion and joy. For Father Nouwen the Eucharist, or thanksgiving, came from above. It was freely offered and therefore could be freely received. A eucharistic life was one lived with gratitude, and the celebration itself prompted ‘a crying out to God for mercy, to listen to the words of Jesus, to invite him into our home, to enter into communion with him and proclaim good news to the world; it opens the possibility of gradually letting go of our many resentments and choosing to be grateful’. (2)

At the Protestant-founded Yale Divinity School in the 1970s and ear1y 1980s, the Catholic professor’s daily Masses were packed every evening, seminarians squeezing into the octagonal basement chapel where the grey stone walls, wicker chairs and icons gave a sense of prayer and intimacy. Michael Christensen, now assistant professor of spirituality at Drew University, New Jersey, was one of the many who attended. This evangelical student soon found himself entering a bewildering new liturgical world with Father Nouwen as a mentor:

Every day I would go to his Mass with the Catholics and the Protestants in that cave-of-the-heart room. On Monday nights I would join the group in his house where we talked and chanted psalms, and I took one of his courses on contemplative Spirituality every semester. When I graduated, Henri advised me to take a retreat in a Trappist monastery, so I went for 30 days as a monastic associate. I emerged from that month-long experience of spiritual direction with new and profound insights into my vocation. From that day, I have gone on a retreat once a year.

But whatever their religious backgrounds, Nouwen sensed that there was always a danger of Christian leaders becoming tempted by individual heroism and forgetting that ministry should always be a communal and mutual experience. Just as ministers should be steeped in contemplative prayer, so he believed they should always be willing to confess their own brokenness and ask for forgiveness from those to whom they ministered. He believed that the sacrament of confession should be a real encounter ‘in which the reconciling and healing presence of Jesus can be experienced’. (3)

Nouwen himself regularly made and heard confessions. Once, when staying at his father’s house in Holland. Henri decided to go to a neighbouring village to make his confession to a priest who had (Nouwen believed) a particular gift as a confessor. When he came out Nouwen expressed not only relief and joy, but also distress because he had apparently been the first priest in seven years to go to that man for confession. Here was somebody with a rare charism for helping people experience the mercy of God, and no one wanted it.

As a confessor himself, Nouwen had a special gift. Brother Christian, of the Abbey of the Genesee in upstate New York, whom Nouwen got to know during his stays there, has vivid memories of making his confession to Father Nouwen on Holy Saturday 1979:

I’ll never forget it. His voice was low and he embraced my feelings. I walked out of there as if it was really something. It lasted 45 minutes and it wasn’t easy, but it was one of the greatest times that I ever made use of the sacrament of penance. He didn’t do a lot of talking but it was a beautiful experience because he had the ability to put you at rest.

But what was so special about Nouwen’s approach to spirituality, and how presumptuous is it to call him a mystic? Nouwen dearly had a great gift for articulating what was in his heart, and felt that it would profit his fellow Christians if he shared his insights, much in the way that Julian of Norwich felt compelled to share her mystical experiences so as to edify and give pleasure to her fellow Christians. Henri was perhaps a mystic in the making. But in his monastic experiences at the Abbey of the Genesee he embraced the mystical dimension, and spirituality became his theology and psychology.

Nouwen saw the human heart as the centre of being, a sacred space within all people ‘where God dwells and where we are invited to dwell with God’. (4) As the mind descended into the heart, through contemplative meditation (for example, by using the Jesus Prayer), so a person’s core identity could progressively conform to the image of Christ. Through spiritual practice, that person could enter into the heart of God. For Nouwen, the heart was that place where humanity and divinity touched, the intersection of heaven and earth, where the finite heart of humanity was mystically unified with the infinite heart of God. Henri Nouwen tried to look at people and the world with the eyes of God, speaking and writing from the place of divine-human encounter. He called it speaking ‘from eternity into time’. (5) But to stay close to God meant being near to the person of Jesus, to whom he was utterly devoted and whose spirit he saw most strikingly at work in the poor, the disadvantaged and the marginalised. Real theological thinking was thinking with the mind of Christ, not engaging in what he termed pseudo-psychology, pseudo-sociology and pseudo-social work, psychology, sociology and much theology, he argued, asked questions ‘from below’, shedding light only in one realm of reality. Real theology was theo-logia, the personal and prayerful study of God, which could access answers ‘from above’, of the higher, deeper eternal realm. These positions were not literal, but were symbols of divine and human sources of wisdom and understanding.

When Nouwen was in Rome, experiencing many complicated issues as a priest, he sought advice from Mother Teresa of Calcutta who was also visiting the city. After he had shared his anxieties with her for ten minutes, Mother Teresa said simply but profoundly, ‘Well, when you spend one hour a day adoring your Lord, and never do anything which you know is wrong … you will be fine! (6) Nouwen later explained that Mother Teresa had ‘punctured my big balloon of complex self-complaints and pointed me far beyond myself to the place of real healing’. (7) He had raised a question ‘from below’ and she had given him an answer ‘from above’. At first, the response had not seemed to fit his question, but then he had begun to see that her answer had come from ‘God’s place and not from the place of my complaints’, (8)This convinced Nouwen that most of the time people responded to questions from below with answers from below. The result was more questions and more answers, and often more confusion.

He liked to meditate on the words of Mother Teresa, as he did on the Writings of Therese of Lisieux and Charles de Foucauld, But Nouwen’s chief theological source was always the Bible, and in particular the Gospel of St John where he found the most intimate connections with his own prayer life. Among his other influences were John Henry Newman whose sermons preached at St Mary’s, Oxford before Newman’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, had impressed Nouwen as a seminarian. Newman’s Apologia pro vita sua and his Idea of a University also made their mark, as did A Grammar of Assent in which Newman defended theology. While theology could be regarded as a mere intellectual exercise, separate from the life of faith, its formulas nevertheless clarified for worshippers the object of their imaginations and affections – God. But while theology dealt in intellectual truths, the practice of faith embraced, with the imagination and the heart, the living truths about the nature of God. Nouwen said it was this distinction between personal experience and intellectual abstraction (between ‘real’ and ‘notional’ assent to God’s truths) which had set him on the mystical path and underlain much of his spiritual theology. (9)

The writings of Thomas Merton and his skilful harnessing of concrete issues of the day with the spiritual life were also significant especially the books Seeds of Contemplation, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, The Sign of Jonas and Zen and the Birds of Appetite. For Merton the contemplative life had been one of constant movement from opaqueness to transparency, and for Nouwen too it was a life with a vision – just as ministry was a life in which that vision was revealed to others. The great mystery was not that people saw God in the world but that God, within each person, recognised God in the world. Ultimately it was about divine self-recognition. Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother, Thea, increasingly affected Nouwen’s deeper emotional life:

Although Vincent van Gogh is certainly not a religious writer in the traditional sense of the word, for me he was a man whose spirit touched my spirit very deeply, and who brought me in touch with some aspects of the spiritual life that no formal spiritual writer ever did. (10)

Another influence on Nouwen’s spirituality was the Hesychastic tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church – the writings of the Desert Fathers, the early monks of Mount Sinai, the tenth-century monks on Mount Athos and the brothers who wrote in nineteenth-century Russia. For him, the Philokalia and The Art of Prayer were its most important expressions. Nouwen said that he had probably learned more about the spiritual life from that tradition than from any Western spiritual writers. He was particularly struck by the writings of one Desert Father, Evagrius Ponticus, who saw the contemplative life as one which began to see the world as transparent, pointing beyond itself to its true nature. The contemplative was someone who saw things for what they really were. who saw the real connections, who knew, as Merton used to say. ‘what the scoop’ is. (11)

Henri Nouwen felt a natural affinity for Russian Orthodox spirituality and culture. He always remembered a conversation with an orthodox priest who had said to him that Western Christianity’s problem was that its theology was not done on the knees. He naturally identified, then, with the Orthodox insight that the true theologian was the person who prayed – and the person who really prayed was the theologian. However, the strong influence of Eastern Christian spirituality on his own life really did not really strike home until 1993 when he visited Ukraine. a country in which he took a keen interest and for whose suffering people he felt deep compassion. One morning there it dawned on him just how much his love of prayer, the liturgical life and sacred art, especially icons, had been nurtured by the Christian East. The trip became a pilgrimage to the source of his Spiritual life. He realised why the famous book about the Jesus Prayer, The Way of the Pilgrim, had had such a deep effect on him: it recounted the story of a peasant who walked through the country visiting holy places in Ukraine saying nothing but ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me’. The prayer gradually moved from his lips to his heart until it had become one with his breathing. Wherever the peasant went, he radiated love and goodness and saw how people’s lives changed through meeting him. Nouwen admitted that his own prayer life had many highs and lows, but somehow the Jesus Prayer had never abandoned him even during his driest periods. It had kept him connected with Jesus, especially during times when little else seemed to. (12)

Although he worshipped in the West and was nurtured daily by the Eucharist of the Latin rite, he had occasional contact with the liturgy of St John Chrysostom which had given him a deep understanding of being in the world without being of it, a sense of being in heaven before leaving earth. There too he had discovered icons, not as illustrations, decorations or ornaments, but as windows on the eternal. At first they had seemed forbidding but as he had started to pray before them they gradually revealed their secrets and drew him away from his daily preoccupations and. as he discerned it, into the kingdom of God,

One of Nouwen’s Orthodox friends, John Garvey, a priest in New York, was a convert from Catholicism. He explained that, after Vatican II. Nouwen was disturbed and discouraged by the move away from the transcendent – the sudden decline of interest in the Church, and the politicisation of Christianity in the form of a struggle between the forces of the left and the right. Part of Nouwen’s attraction to Orthodoxy, he suggested, was the idea of an alternative approach to Christianity in which one could have a deep sense of freedom and at the same time a deep sense of fidelity to tradition:

Both of these things appealed to him greatly and he understood that they did not need to be contradictory. He found something of that in Orthodoxy which appealed to him, espectally when he looked at the clarity of the Desert Fathers or the Fathers of the Church. He saw that it understood the psychology of Spirituality at that incarnate level, without needing the jargon of contemporary psychology. At the same time, unlike any psychology, it was capable of looking at the cross and the hope of resurrection. Henri was a curious, questing soul. Once he began to be interested in Orthodoxy, he came to see how integral icons were to its worship. I think he saw in icons something profoundly helpful to prayer, especially in the way they could become the focus of an interior stillness.

Nouwen did not draw extensively on non-Christian spirituality, although he valued the writings of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and liked to quote Jewish stories when illustrating points about the spiritual life. The same was true with tales of Zen Buddhist enlightenment. During the early 1970s he had marched alongside Buddhist monks in anti-Vietnam War protests but this never led him to take much of an interest in the East, as van Gogh had done, or to explore Oriental spirituality with anything like the vigour of Merton, although he did have a genuine respect for the Dalai Lama. In later years, though, he visited the Hindu meditation master. Eknath Easwaran, in California, taking some of his contemplative insights into his own prayer life, and quoted Ramakrishna as an important spiritual figure.

While he drew on rich spiritual resources, his own contemplation was born of much inner conflict. Colleagues and friends did not regard him as a mystic in the modem sense of being gifted with extraordinary graces: he was not a man of easy prayer but he wasn’t a person of illusions either. He wasn’t mystical in the sense of ‘ecstasies’; he was, however, a mystic in the traditional sense of being deeply spiritual. Nouwen was a priest who tried to follow the mystical path through earnest prayer and a disciplined sacramental life focused on the Eucharist. He read Scripture carefully, studied many of the spiritual classics and was drawn to God through icons and other forms of art. His was fundamentally a theology from the knees but, in spite of his faithfulness, the practice of prayer did not come easily to a man of such distracted temperament. His deepest contemplative moments often came when he was writing: these were times of solitude and centring for him.

Notes

Mystical Path

1. Henri J. M. Nouwen, In the Name of Jesus (London. Darton, Longman and Todd.1989). pp. 30-31.

2. Henri J. M. Nouwen, With Burning Hearts (London, Geoffrey Chapman. 1994).pp. 93-4.

3. In the Name of Jesus, p. 46.

4. Henri J. M. Nouwen, Here and Now (London. Darton. Longman and Todd. 1994).p.8.

5. Henri J. M. Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son (London. Darton. Longman and Todd. 1994). p. 17.

6. Here and Now. p. 75.

7. ibid.

8. ibid.

9. Fred Bratman and Scott Lewis, The Reader’s Companion (New York. Hyperion, 1994). p. 74.

10. ibid.

11. Henri J. M. Nouwen, Clowning in Rome (New York. Image, 1979), p. 88.

12. As described in Henri J. M. Nouwen, ‘Pilgrimage to the Christian East, Ukrainian Diary Part 1′, New Oxford Review (April 1994). p. 14.

Bibliography

Intimacy: Pastoral Psychological Essays (Fides. 1969; Harper & Row. 1981)

Creative Ministry: Beyond Professionalism in Teaching. Preaching. Counseling. Organizing and Celebrating (Doubleday. 1971)

With Open Hands (Ave Marta. 1972. new revised edition. 1995)

Thomas Merton: Contemplative Critic (Fides. 1972; Harper & Row. 1981)

The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society (Darton. Longman and Todd. new edition. 1994)

Aging: FulfIllment of Life. co-authored with Walter Gaffney (Doubleday. 1974)

Out of Solitude: Three Meditations on the Christian Life (Ave Marla. 1974)

Reaching Out: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life (Fount, new edition. 1996)

The Genesee Diary: Report From a Trappist Monastery (Darton. Longman and Todd. new edition. 1995)

The Living Reminder: Service and Prayer in Memory of Jesus Christ (Seabury. 1977: Harper & Row. 1983)

Clowning in Rome: Reflections on Solitude. Celibacy. Prayer and Contemplation (Doubleday Image. 1979)

In Memoriam (Ave Marta. 1980)

The Way of the Heart: Desert Spirituality and Contemporary Ministry (Darton. Longman and Todd. third edition. 1999)

Making All Things New: An Invitation to the Spiritual Life (Harper & Row. 1981)

A Cry for Mercy: Prayers From the Genesee (Doubleday. 1981)

Compassion: A Reflection on the Christim Life. co-authored with Donald P. McNeill and Douglas A. Morrison (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1982)

A Letter of Consolation (Harper & Row. 1982)

jGracias!: A Latin American Journal (Harper & Row. 1983; Orbis. 1992)

Love in a Fearful Land: A Guatemalan Story (Ave Maria. 1985)

In the House of the Lord: The Journey from Fear to Love (Darton. Longman and Todd.1986)

Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons (Ave Maria. 1987)

Letters to Marc About Jesus (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1988)

The Road to Daybreak: A Spiritual Journey (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1989: memorial edition. 1997)

Circles of Love: Daily Readings with Henri J. M. Nouwen. edited by John Garvey (Darton.Longman and Todd. 1988)

The Primacy of the Heart: Cuttings from a Journal. edited by Lewy Olfson (St Benedict Center. 1988)

Seeds of Hope: A Henri Nouwen Reader. edited by Robert Durback (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1989. new edition. 1998)

In the Name of Jesus: Reflections on Christian Leadership (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1989)

Heart Speaks to Heart: Three Prayers to Jesus (Ave Marla. 1989)

Beyond the Mirror: Reflections on Death and Life (Crossroad. 1990)

Walk with Jesus: Stations of the Cross (illustrations by Sr Helen David: Orbis. 1990)

Show Me the Way: Readings for Each Day of Lent. edited by Franz Johna (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1993)

The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1994)

Life of the Beloved: Spiritual Living In a Secular World (Hodder and Stoughton. 1993)

Jesus and Mary: Finding Our Sacred Center (St Anthony Messenger Press. 1993)

Our Greatest Gift: A Meditation on Dying and Caring (Hodder and Stoughton. 1994)

With Burnlng Hearts: A Meditation on the Eucharistic Life (Geoffrey Chapman. 1994)

Here and Now: Living In the Spirit (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1994)

Path Series: The Path of Waiting / The Path of Power / The Path of Peace (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1995): The Path of Freedom (Crossroad. 1995)

Ministry and Spirituality: Three Books In One (Continuum. 1996)

Can You Drink the Cup? The Challenge of the Spiritual Life (Ave Maria. 1996)

The Inner Voice of Love: A Journey Through Anguish to Freedom (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1997)

Bread for the Journey: Thoughts for Every Day of the Year (Darton. Longman and Todd.1997)

Spiritual Journals: Three Books In One (Continuum. 1997)

Adam: God’s Beloved (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1997)

The Road to Peace: Writings on Peace and Justice. edited by John Dear (Orbis. 1998)

Sabbatical Journey (Darton. Longman and Todd. 1998)