Summary: Edith Stein, martyr, was born into the Jewish faith on 12 Oct. 1891, in the city of Breslau, Poland. Edith Stein converted to Catholicism and entered the Carmelite convent taking the religious name Mary of the Cross.

Edith Stein was a Jewish philospher, a disciple of Husserl, who converted to Catholicism and entered the Carmelite community in Cologne. Although she moved from Cologne in Germany to Echt in Holland, she was eventually arrested by the Nazis and died at Auschwitz in 1942. Canonised by Pope John Paul II, she is also honoured as patron of Europe.

Edith Stein was a Jewish philospher, a disciple of Husserl, who converted to Catholicism and entered the Carmelite community in Cologne. Although she moved from Cologne in Germany to Echt in Holland, she was eventually arrested by the Nazis and died at Auschwitz in 1942. Canonised by Pope John Paul II, she is also honoured as patron of Europe.

Fr John Murray PP traces her spiritual odysey.

‘I picked a book at random and took out a large volume. It bore the title The Life of St. Teresa of Avila. I began to read, was at once captivated, and did not stop till I had reached the end. As I closed the book – it was already dawn – I said, “This is the truth”.’

The following day, the reader went to the local church and asked to be baptised. The elderly priest asked her, ‘How long have you been taking instruction?’ ‘Please, Father,’ she replied, ‘test my knowledge.’ And he did, extensively. At the end, the priest was astonished by her accurate answers and, on New Year’s Day 1922, Edith Stein was baptised into the Catholic faith. She chose Teresa as her baptismal name, and later that day she received the Eucharist for the first time.

Difficult Path

The road to faith in Jesus Christ was not an easy one for Edith. The youngest in her family, she was born into the Jewish faith on 12 October 1891, in the German city of Breslau, now Wroclaw, in Poland. Her father died when she was young, and her mother, Auguste, raised her seven children and ran the family timber business, even into her eighties. She was an impressive woman, who was proud of her Jewish traditions and faith.

By the age of twenty-one, Edith was a self-confessed atheist. To placate her mother, she continued to attend the synagogue, but she felt nothing there. In the meantime, she had excelled at her studies, and in 1916, after completing her doctoral thesis in philosophy, she became assistant to the great professor of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl.

Jolt to the System

It was while she was with Husserl that Edith received the first jolt to her convinced atheism. A friend of hers, Adolf Reinach, a fellow philosopher at Göttingen, had died, and his widow had requested Edith to sort out his papers. Edith got a profound shock when she discovered how this Christian woman accepted the cross of Adolf’s death.

Later Edith wrote, ‘It was then that I first encountered the cross and the divine strength which it inspires in those who bear it. It was the moment in which my unbelief was shattered. Christ streamed out upon me: Christ in the mystery of the cross.’

Breaking the News

It was at Göttingen also that she came into contact with Hedwig Conrad-Martius and his wife. It was in their house, one night when they had gone out to a function, that Edith picked up the volume of St. Teresa’s life and began to read. Hedwig later stood for her at her baptism.

Shortly after this event, Edith knew she could not keep her secret from her mother, and told her, ‘Mother, I am a Catholic’. Auguste wept, and Edith with her. Later, a friend wrote about Auguste at this time, ‘As a God-fearing woman, she sensed without realizing it the holiness radiating from her daughter and, though her suffering was excruciating, she clearly recognised her helplessness before the mystery of grace’.

Shortly after this event, Edith knew she could not keep her secret from her mother, and told her, ‘Mother, I am a Catholic’. Auguste wept, and Edith with her. Later, a friend wrote about Auguste at this time, ‘As a God-fearing woman, she sensed without realizing it the holiness radiating from her daughter and, though her suffering was excruciating, she clearly recognised her helplessness before the mystery of grace’.

A Silent Place

Edith spent the next few years at the Dominican convent in Speyer. There she taught German in exchange for a room and the meagre convent food. ‘She quickly won the hearts of her pupils,’ a sister wrote about her. ‘In humility and simplicity almost unheard and unnoticed, she went quietly about her duties, always serenely friendly and accessible to anyone who wanted her help.’ The world outside also wanted Edith. Her scholarship had not gone unnoticed, and so she went out regularly to give lectures to an appreciative public.

Lectures, publications and other work continued to multiply but, in the midst of it all, a life of deep prayer was growing. ‘There is no sense in rebelling against it,’ she wrote. ‘It is merely necessary that one should, in fact, have a silent corner in which to converse with God, as if nothing else existed, every day.’

New life

By late 1932, the situation was becoming more and more difficult in Germany, especially for Jews. In January 1933, Hitler came to power and set up the Third Reich. The Nazis began to pass laws which were designed to marginalise non-Aryans from public life. On 23 February 1933, Edith gave her last lecture.

As one door closed, another seemed inexorably to open. The desire for religious life, which she had felt for years, now began to flourish. In May 1933, she visited the Carmel in Cologne, and on 14 October, the eve of the feast of St. Teresa, her baptismal patron, she entered the convent.

Young sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, was born into a Jewish family in Breslau, Germany

The famous philosopher and lecturer now became the novice. Her tastes had always been simple, but now her little cell, no more than ten feet square, contained nothing but a straw mattress, a water jug, a few unframed pictures of Carmelite saints, and a plain wooden cross on the wall. Such was the decor of a Carmelite cell. Here was the battleground where daily the nun struggled against her own self-interest until her nature was wedded to grace.

On 15 April 1934, Edith was clothed in the habit, and took the name she herself had suggested, Sr. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. The following year, on Easter Sunday, she made her profession. ‘How do you feel?’ someone asked. ‘Like the bride of the Lamb!’ was her reply.

Time Running Out

If 1935 brought much joy, the following year brought sorrow. Initially, her mother had not returned Edith’s weekly letters. In time, however, Edith learned that Auguste had begun to visit a local Carmel secretly, and soon she began to write to her daughter. There was not a lot of time, however, for Auguste died later that year, but Edith was so glad that mother and daughter had become reconciled before the end came.

As the Nazis gained a stranglehold on the life of the nation, the situation in Germany continued to deteriorate. A decision was made that Edith and Rosa, her sister who had followed her into the Church and Carmel, should leave Cologne and move to Echt in Holland. Holland too was in the grip of the Nazis, however, and many Jews were being deported to the Polish concentration camps and to certain death.

In July 1942, the Dutch bishops issued a letter condemning the treatment of the Jews. They urged the faithful to examine their consciences, and to pray for divine help. The German authorities were displeased at the bishops’ audacity, and on 2 August all non-Aryan people were arrested. It was a reprisal for the letter, the German commissar said.

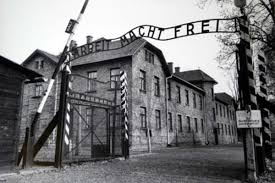

Auschwitz

That very afternoon, two SS officers arrived at the convent, and Edith was arrested, together with Rosa. From Echt, she was brought to Auschwitz extermination camp, in Poland. She never returned, for her life, and Rosa’s, ended there on 9 August 1942, just a few days after their arrest.

That very afternoon, two SS officers arrived at the convent, and Edith was arrested, together with Rosa. From Echt, she was brought to Auschwitz extermination camp, in Poland. She never returned, for her life, and Rosa’s, ended there on 9 August 1942, just a few days after their arrest.

Even in those terrible final days, however, she had work to do. A Jewish businessman who knew her in the camp wrote later, ‘Sr. Benedicta at once took charge of the poor little ones, washed and combed them, and saw to it that they got food and attention’.

Another fellow prisoner said, ‘She was thinking of the sorrow she foresaw: not her own sorrow – for that she was far too calm – but the sorrow that awaited others. Her whole appearance suggested only one thought to me: a pietà without Christ’.

Today, Auschwitz stands pristine in its condition, preserved as a museum by the Polish nation, as if frozen in time from the moment the Nazi guards left it. It is a painful reminder to the world of the evil power of racism. Like the millions of others, no stone marks Edith’s grave.

Beatification

Beatification

In 1998 Pope John Paul canonised her as a saint, with a feast on the ninth of this month. On that occasion, the Pope said, ‘The modern world boasts of the enticing door which says everything is permitted. It ignores the narrow gate of discernment and renunciation. She is one of the Patrons of Europe.

‘I am speaking to you, young Christians. Your life is not an endless series of open doors! Listen to your heart! Do not stay on the surface, but go to the heart of things! And when the time is right, have the courage to decide! The Lord is waiting for you to put your freedom in his good hands.’

Edith would surely have added: ‘This is the truth’!

This article first appeared in The Messenger (August 2005), a publication of the Irish Jesuits.

******************************

Memorable Wisdom for Today

The nation… doesn’t simply need what we have.

It needs what we are.

~ Edith Stein ~

******************************