By Sarah Mac Donald - 20 September, 2013

The Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin has appealed for a full debate between the country’s churches and the Government on denominational education.

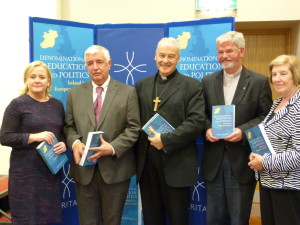

In his address at the launch of ‘Denominational Education and Politics: Ireland in a European Context’ by Jesuit Fr David Touhy at the Milltown Institute in Dublin on Wednesday night he underlined that this debate would have to leave aside “lazy caricatures” and “axes to grind.”

Speaking to educationalists and academics, the Anglican churchman said Fr Touhy’s book subtly and comprehensively sets out its thesis in such a way that a theological rationale for education is distinguished from a denominational expression of it.

This allowed any faith community “to lift itself above the brick wall of self-pity and to ask critical questions of itself regarding credibility and viability.”

“Faith communities need to do this, whether they actually want to or not,” he stated. This approach also opened the pathway to ask the same and different questions of secular society which is “the paymaster of the educational system” he said.

“Somehow, our theological nerve is not strong enough for us to celebrate God. Somehow, our suspicion of secularisation is that, at the end of the day, it is value-void,” he commented.

Describing Ireland, North and South, as an “over-denominationalised country”, the Archbishop questioned whether it was sufficiently mature as a democracy to debate respectful accommodation of diversity within the educational system.

The Anglican churchman said David Tuohy’s theological confidence comes through on every page. “It enables him to be critical of denominational assumptions as well as of state provisions.”

He also asked if Irish society was capable of sustaining “clear water between religious education and denominational catechesis?” The ethos of a school should not be threatened or “mauled by insecure religiosity,” he warned.

His question was whether contemporary Ireland is sufficiently mature to have this debate about ‘the promotion of the human person,’ in which accommodation of diversity forms and frames the ground rules or “are we still too fond of the tired caricatures whether they be those of secularization or of religiosity” he asked?

Describing the current debates around education in Ireland as the watering hole at which arguments about the existence or non existence of God were focused, he noted that there was a strong undercurrent in the current debate on education “that the rejection of God is a requirement for a modern and scientific society.”

On state provisions, he asked how the state supports different groups’ right to religious freedom within the education system. “Is a self-consciously secularising state sufficiently open about its mission in a post-religious society,” he asked.

Challenging some of denominational assumptions, he questioned, “Is a self-protective church sufficiently clear and clean about its mission of evangelisation.”

He expressed concern over the inability of the current system of exemption to operate in a satisfactory way for those who wish to opt out of religious education.

The theological battles of a country caught painfully by its history between the sacred and the secular are fought out in a trench warfare in education and healthcare, he said.

Our theological nerve is not strong enough for us to celebrate God, he said and added “our suspicion of secularisation is that at the end of the day it is value void.”

Our theological nerve is not strong enough for us to celebrate God, he said and added “our suspicion of secularisation is that at the end of the day it is value void.”

“Religion and politics need to meet and converse if education is to flourish rather than flounder,” he warned.

At the launch in Milltown, Jesuit provincial, Fr Tom Layden described ‘Denominational Education and Politics: Ireland in a European Context’ as “a really important book that can contribute enormously to the often contentious and challenging debate on the future of Irish education.”

He gave an insight into the historical context in which the Jesuits worked out a methodology for teaching which gave students the very best education through the Ratio Studiorum, the first school curriculum, which became a globally influential system of education.

In his address, he said Fr David Tuohy, as an educationalist and Jesuit, is part of that tradition and his book is another fruit of the labour.

“His influence and success in what he has achieved to date is also, I believe, due to his methodology – so like that of those early Jesuits,” he suggested and he commended Fr Tuohy’s ten years of work with the Le Cheile Schools Trust.

That process or methodology embodies the kind of openness, depth, rigour David wants us to put into the debate on education which we should be having and he forcefully reminds us we are not having in Ireland today.

He referred to Fr Tuohy’s identification of a lack of clarity and agreed meaning around key terms being used in the debate.

People speak about ‘ the common good’, ‘religious freedom’ even ‘catholic education’ as if they all know what each other is referring to. It is most helpful when David clarifies the confusion and often contradictions inherent in the terms people use in so called ‘common discourse’, he said.

In the multi-cultural Ireland of today, an Ireland of many faiths and none, it is vital to have David Tuohy’s analysis of and clarity around the concepts in the debate, Fr Layden suggested.

Equally valuable is the historical and wider geographical context in which he elucidates these concepts. In his effort to broaden and deepen the current debate in Ireland, he draws on the political context of Europe to examine issues such as the aforementioned separation of church and state and religious freedom and education.

One of his findings, Fr Layden noted, was that many European countries, in spite of their secular ethos, are almost as vigorous in their support of denominational education as of state education.

“They endorse the right of parents to educate their children in accordance with their world view, be it religious or secular, and they have a strong commitment to the notion of religious freedom,” he said.