By Cian Molloy - 09 February, 2020

“No Irish Need Apply” discrimination was suffered mostly by those who had names that were easily identified as

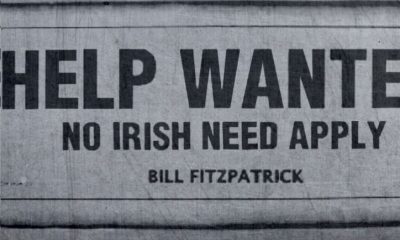

“No Irish Need Apply”, a sectarian stipulation in some US advertising 150 years ago.

“Catholic”, reveals a new study of US census data from the nineteenth century.

It is easily forgotten, how anti-Catholic the United States was 150 years ago, when the Know Nothing Party in Boston, for example, campaigned on an anti-Catholic ticket and where Irish Catholics were perceived as a threat by the majority Protestant population. Newspaper advertisements for situations vacant often included the line “No Irish Need Apply”, reducing opportunities for Irish new arrivals in America’s fabled “land of opportunity”.

Research published this week by William Collins and Ariell Zimran of the Vanderbilt University in Tennessee reveals just how closely anti-Irish discrimination was linked to anti-Catholic discrimination.

Comparing the job titles of fathers with those of sons in US census data as a way of tracking social mobility, the researchers found that “having a more Catholic surname and being born in Ireland were associated with less upward mobility”.

This is a new insight, although discrimination based on Christian names was commonly known about and understood, as illustrated by the lyrics of a song No Irish Need Apply written by John Poole in 1878 when Ireland’s famine emigrants were starting to achieve successes in America. The song includes a line: “Some may think it a misfortune to be Christened ‘Pat’ or ‘Dan’, but for me it is an honour to be called an Irishman.”

The middle of the nineteenth century was at a time when many believed “Protestantism defined American society” and that “Catholicism was not compatible with the basic values Americans cherished most”. These people believed their values were threatened by the arrival of thousands of Catholics fleeing famine in Ireland, just as many Americans today fear the arrival of Muslim refugees fleeing war in the Middle East.

In the 1850s, naked sectarianism was undoubtedly one reason why Irish Catholics did not do as well as their Protestant country men in the New World, but other factors were also in play, caution Collins and Zimran.

For example, before the famine, most Irish emigration to the United States came from Ulster and Leinster, but once the potato crop failures began in earnest, the bulk of Irish emigration was from Munster and Connacht. It is speculated that because of this “the characteristics of migrants may have changed because residents of the South and West were more agricultural and less literate than elsewhere”. Collins and Zimran add: “They were also more likely to be Catholic and to speak Irish.”

Notably, the research also found “children born in Ireland, even those who spent nearly their entire life in the US, fared worse that those born in the US, potentially reflecting exposure to famine conditions”.

Collins and Zimran comment that their study gives insights into how America welcomed “the largest wave of disaster refugees that the US has ever absorbed” and they claim that their paper “provides a useful historical perspective at a time when refugees are once again viewed by many with scepticism and scorn”.