By Susan Gately - 06 February, 2015

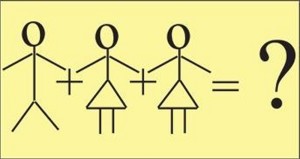

On Tuesday the British parliament voted to allow the creation of IVF babies with DNA from three parents.

On Tuesday the British parliament voted to allow the creation of IVF babies with DNA from three parents.

Carried by 382 to 128 in the House of Commons, the law will make Britain the first country in the world to permit IVF babies to be created using biological material from three different people.

The genetic watchdog Human Genetics Alert has warned of “the risk of a consumer eugenic market in ‘enhanced designer babies’.”

The debate centred on mitochondrial DNA donation techniques aimed at preventing serious diseases from being passed from mother to baby.

Hereditary mitochondrial diseases affect major organs and cause symptoms ranging from poor vision to diabetes and muscle wasting.

In the UK it is estimated that 2,500 women are affected by mitochondrial diseases and could use the technique.

The Catholic and Anglican Churches in England, and groups like Human Genetics Alert (HGA) opposed the law.

The Churches argued that the idea was not safe or ethical, not least because it involved the destruction of embryos.

Human Genetics Alert said the move would open the door to further genetic modification of children in the future – so-called designer babies, genetically modified for beauty, intelligence or to be free of disease.

In a statement after the vote on Tuesday, Bishop John Sherrington, on behalf of the Bishops Conference of England and Wales, said the Church remained opposed on principle to these procedures “where the destruction of human embryos is part of the process.”

In a statement after the vote on Tuesday, Bishop John Sherrington, on behalf of the Bishops Conference of England and Wales, said the Church remained opposed on principle to these procedures “where the destruction of human embryos is part of the process.”

“This is about a human life with potential, arising from a father and a mother, being used as disposable material,” he said.

“The human embryo is a new human life with potential; it should be respected and protected from the moment of conception and not used as disposable material.”

A free vote was allowed on the bill, with the opposition being led by Conservative MP Fiona Bruce.

She said she believed the regulations failed on the counts of both ethics and safety.

“One of these procedures we are asked to approve today, pronuclear transfer, involves the deliberate creation and destruction of at least two human embryos, and probably in practice many more, in order to create a third embryo which it is hoped will be free from human mitochondrial disease.

“Are we happy to sacrifice two early human lives to make a third?” she asked.

Dr David King, Human Genetics Alert

HGA has campaigned against plans to legalise ‘mitochondrial transfer’ techniques for prevention of mitchondrial genetic diseases from 2012 saying the techniques would be the first instance of “deliberate changes to the germ line of children: the changes would be present in all cells of the body and would be transferred to descendants of girls created using the technique.”

The watchdog says there has been a strong international consensus for the last 20 years, because of “the risk of a consumer eugenic market in ‘enhanced designer babies’.

Although the techniques are not the same as genetic modification, once this line has been crossed it will become difficult to oppose genetic modification,” states its website.

Dr David King, director of HGA warned that the change in the law was the beginning of a slippery slope.

“Advocates say we shouldn’t worry about ‘slippery slopes’. Yet in my experience, they are the very same people who, a few years later, push us to take the next step and the one after that. If we want to avoid the nightmare designer baby future we must draw the line here.”