– 17th September 2023 –

Gospel reading: Matthew 18:21-35

vs.21 Peter went up to Jesus and said:

“Lord, how often must I forgive my brother if he wrongs me? As often as seven times?”

vs.22 Jesus answered, “Not seven, I tell you, but seventy-seven times.

vs.23 And so the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who decided to settle his accounts with his servants.

vs.24 When the reckoning began, they brought him a man who owed ten thousand talents;

vs.25 but he had no means of paying, so his master gave orders that he should be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, to meet the debt.

vs.26 At this, the servant threw himself down at his master’s feet. ‘Give me time’ he said, ‘and I will pay the whole sum.’

vs.27 And the servant’s master felt so sorry for him that he let him go and cancelled the debt.

vs.28 Now as this servant went out, he happened to meet a fellow servant who owed him one hundred denarii; and he seized him by the throat and began to throttle him.

vs.28 Now as this servant went out, he happened to meet a fellow servant who owed him one hundred denarii; and he seized him by the throat and began to throttle him.

‘Pay what you owe me’ he said.

vs.29 His fellow servant fell at his feet and implored him, saying, ‘Give me time and I will pay you.’

vs.30 But the other would not agree; on the contrary, he had him thrown into prison till he should pay the debt.

vs.31 His fellow servants were deeply distressed when they saw what had happened, and they went to their master and reported the whole affair to him.

vs.32 Then the master sent for him.

‘You wicked servant,’ he said. ‘I cancelled all that debt of yours when you appealed to me.

vs.33 Were you not bound, then, to have pity on your fellow servant just as I had pity on you?’

vs.34 And in his anger the master handed him over to the torturers till he should pay all his debt.

vs.35 And that is how my heavenly Father will deal with you unless you each forgive your brother from your heart.”

****************************************************************

We have four sets of homily notes to choose from. Please scroll down the page for the desired one.

Michel DeVerteuil : Holy Ghost Priest, Teacher in Lectio Divina

Thomas O’Loughlin: Professor of Hist Theol, Uni of Nottingham.

John Littleton: Director, Priory Institute, Tallaght, Dublin 24

Donal Neary SJ: Editor of The Sacred Heart Messenger

****************************************

Michel DeVerteuil

Lectio Divina with the Sunday Gospels- Year A

www.columba.ie

General Comments

Today’s passage deals with the crucial issue of forgiveness, surely the most pressing of all our human problems, as individuals, as communities and as a human family. The future of humanity is in the hands of those who can forgive.

It is important to understand Peter’s question correctly: it is not about being wronged many times (a situation which Jesus speaks about in Luke 17:4). Here, Peter is asking about one wrong. We are dealing then with a very deep hurt, the kind that remains with us for years and that we find ourselves having to forgive many times over. We think we have forgiven, but when we meet the person who hurt us we realise that we have to start forgiving all over again. This is the question then – how long do we continue with this struggle to forgive the one wrong?

It is important to understand Peter’s question correctly: it is not about being wronged many times (a situation which Jesus speaks about in Luke 17:4). Here, Peter is asking about one wrong. We are dealing then with a very deep hurt, the kind that remains with us for years and that we find ourselves having to forgive many times over. We think we have forgiven, but when we meet the person who hurt us we realise that we have to start forgiving all over again. This is the question then – how long do we continue with this struggle to forgive the one wrong?

We must think not merely of personal wrongs but of deep ethnic and racial wrongs, the kind that have nations torn by civil strife for generations – the human family knows so many of these at present.

As always, Jesus does not give us prescriptions; he invites us to enter into the God-like way of seeing things and leaves it to us to decide how we will act out of that consciousness.

Jesus’ response is in the form of a parable, and the key to interpreting his message correctly is to understand how a parable is meant to be read.

We are accustomed to learning (and teaching) through “edifying stories.” In this kind of story the characters are either “good” or “bad”; we are meant to imitate the good ones and avoid being like the bad. It is always wrong to read a parable like that. We find that we identify one of the characters with God and end up with a strange God,

1) one who tortures those who don’t forgive their enemies,

2) burns the cities of those who do not accept his wedding invitation, 3) closes the door on the bridesmaids who come late for the wedding feast, and so forth. Many Christians have developed warped ideas of God as a result of reading Jesus’ parables in this way.

A parable is an imaginative story which we enter with our feelings. We identify with the various characters as the story unfolds, until at a certain point it strikes us: “I know that feeling!” This is a moment of truth, when we say, “I now understand grace and celebrate the times when I or others have lived it,“ or “I now understand sin and experience a call to conversion.”

In this parable we see a man who is in a position of total helplessness; he is made to feel worthless, he has neither dignity nor freedom. His life, and that of his entire family, is in the hands of this king who makes him grovel before he will condescendingly set him free of his debts. He is not a bad man: he has been generous enough to lend money to someone who is in even greater need than he is, knowing full well that sooner or later he will have to return his own loan to the king.

The problem with him is that his spirit has been broken by oppression. Hardship has extinguished the spark of generosity. Experience tells us how frequently this happens. He has been made to feel so helpless and impotent that when he finds someone with even less power than himself he oppresses him in turn.

The king also is a victim of oppression. He breaks out of the oppressive world when he forgives his servant (even though we can detect some condescension), but it doesn’t last. The servant’s meanness defeats him, he takes back his generous spirit and becomes as mean as the servant. Very different from our God!

The parable then makes us reflect on oppression, understood quite correctly as being indebted. What a terrible thing oppression is! It keeps everyone in bondage – the oppressed and the oppressors alike. It isn’t God who keeps us in bondage, but we ourselves, and the parable tells us that we will continue in this bondage, “handed over to torturers”, unless someone makes a breakthrough and replaces meanness with generosity of spirit, the spirit of forgiveness, permanent and unconditional, “from our hearts.”

We can reflect on the movement of oppression/forgiveness at different levels

– on the world stage,

– in our countries,

– within our families and neighbourhoods,

– in our own hearts.

In each case, we celebrate the people who have made the breakthrough.

In our own hearts: what unforgiven hurts still “torture” us?

We recognise the bitterness which

– keeps us in bondage,

– consuming our energies,

– preventing us from enjoying life and being at peace with those around us. We remember the times when we were able to free ourselves, even if only temporarily, like the king.

Within families and communities: so often we are concerned mainly about punishing the offender. We celebrate today the peacemakers among us, those who work through mediation to re-establish harmony within the community.

Within families and communities: so often we are concerned mainly about punishing the offender. We celebrate today the peacemakers among us, those who work through mediation to re-establish harmony within the community.

Within nations, especially between ethnic groups, social classes, religions. We think of places like Northern Ireland, former Yugoslavia, the Republic of Congo, Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan, the black community in the United States – the list can go on and on! e.g.Windrush West Indians invited by the British Government and who were later denied their right to citizenship. Stolen goods takes as trophies for the ‘mother country during the colonial and slavery days

We think of the debt of the third world countries, causing anger, resentment and civil strife. On going indifference to the plight of those who are still in debt keeping them in residual bondage.

Prayer Reflection

As we begin our prayer, let us listen to some of the prophetic voices of our time speaking of forgiveness to our modern world which is so much in need of it:

“The philosophy of retributive justice has brought nothing but chaos and widespread distress to families caught up in it. It has guaranteed a growing level of crime and has wasted millions of taxpayers’ money. We need to discover a philosophy that moves from punishment to reconciliation, from vengeance against offenders to healing for victims, from alienation to integration, from negativity and destructiveness to healing and forgiveness. Retributive justice always asks first: how do we punish the offender? Restorative justice asks: how do we restore the well-being of the victim, the community and the offender?” …. Vincent Travers, O.P. in Religious Life Review, Sept./Oct. 1995

“The experience of forgiveness leads us to a radical understanding of the doctrine of Grace. We are saved, not by getting it right, but by the love that redeems us while we are getting it wrong.“... Richard Holloway, Dancing on the Edge

“The experience of forgiveness leads us to a radical understanding of the doctrine of Grace. We are saved, not by getting it right, but by the love that redeems us while we are getting it wrong.“... Richard Holloway, Dancing on the Edge

– “There will come a day when the martyr will be made to stand before the throne of God in defense of his persecutors and say, ‘Lord, I have forgiven in thy name and by thy example. Thou hast no claim against them any more.'”…A Russian Orthodox bishop wrote these words as he went to his death in one of Stalin’s purges

“O Lord, remember not only the men and women of good will, but also those of ill-will. But do not remember all the suffering they have inflicted on us; remember the fruits we have bought thanks to this suffering – our comradeship, our loyalty, our humility, our courage, our generosity, the greatness of heart which has grown out of all this. And when they come to the judgement, let all the fruits that we have borne be for their forgiveness.”

Prayer found in the clothing on the body of a dead child at Ravensbruck Concentration Camp where 92,000 women and children died; in Mary Craig’s, “Take up your Cross,” The Way, Jan. 1973

“While waiting for the Kingdom, make the Kingdom.

While waiting for righteousness and peace, practice righteousness and peace.

You want a paradise of love? Forgive.” …..Carlo Carretto, Summoned by Love

Lord, we ask you to look with compassion on the many people in our world who are held in bondage because they cannot forgive from their hearts.

Pope Francis visiting the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere during a visit to the Sant’Egidio community in Rome

We thank you for the great people of our time who, like Jesus, work for the forgiveness of debts

– John Dear and the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Washington, D.C.;

– the Sant Egidio Community in Rome;

– the Tallaght Community Mediation Scheme in Dublin;

– Archbishop Tutu and the Truth Tribunal in South Africa.

We thank you that these servants, following the way of Jesus,

are showing our contemporaries that unless they forgive from their hearts

you have no choice but to leave them and their communities in bondage.

We thank you for those who have taught our world forgiveness:

– spouses who welcomed back those who had been unfaithful;

– members of minority groups who work for racial harmony in their neighbourhoods;

– devotees of traditional African religions in dialogue with the mainline churches;

– Nelson Mandela;

– Popes John Paul II and Francis.

We thank you that, unlike the king in Jesus’ parable,

they did not let themselves be turned aside from the path of forgiveness,

but forgave seventy-seven times.

Lord, have pity on the many countries that are being torn apart by traditional hatreds; send them men and women who will show their compatriots that unless they forgive from their hearts

they will be forever tortured by hatred and the desire for revenge.

*********************************************************

Thomas O’Loughlin

Liturgical Resources for the Year of Matthew

www.columba.ie

Introduction to the Celebration

We often describe ourselves as ‘the People of God’ and as ‘a people set apart’; and very often such names have been misinterpreted by Christians to mean that we are somehow ‘God’s elite’ or that he has some special friendship for us and our doing that he does not show to others. Today’s gospel confronts us with the reality of what it means to be ‘a people set apart’. We are the ones who must reject the desires for vengeance and retaliation, and in the face of those who offend us must work for reconciliation.

To start afresh, working for what is good, after one has been hurt is never easy; it goes against a deeply embedded instinct in our humanity that calls for retribution. But to be the group who seek to continue the reconciliation of the world that was accomplished in the Paschal Mystery of Jesus is what we are about.  Now, as we begin to celebrate this mystery, let us remind ourselves that as ‘a people set apart’ we must be willing to be those who bring forgiveness and new hope into the world. Let us ask ourselves whether we are willing to be reconcilers.

Now, as we begin to celebrate this mystery, let us remind ourselves that as ‘a people set apart’ we must be willing to be those who bring forgiveness and new hope into the world. Let us ask ourselves whether we are willing to be reconcilers.

Homily Notes

1. Reconciliation is a word that is bandied about in Christian discourse: we talk about it in relation to individual sinfulness; we talk about it in social situations of injustice; and we use it as the name of one of the sacraments: the Sacrament of Reconciliation. We use the word so often that it can become just a synonym for repentance, penance, the process of ‘getting rid of sin’, offering forgiveness, or a process for rebuilding harmony in society. It is all of these things, but it is also one of the key words by which we can understand the role of the Christ in relation to church,

the role of the Christian body towards the larger society, and

the one of the central Christian attitudes towards life and how it should be lived.

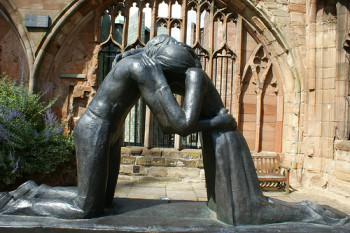

This sculpture is called ‘Reconciliation’. It is in the ruins of the old Coventry Cathedral in England

2. It is easiest to begin by sketching the habit of being reconciliatory, being someone with the attitude of wanting reconciliation. It is worth noting the exact implications of Peter’s question of Jesus: ‘Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? As many as seven times?’ There is no hint in the text that this brother has come and asked for forgiveness. This is not a mutual process. The forgiveness in question is a unilateral act by the one who has been sinned against. Someone has been offended/ attacked; that person now wants to forgive the offender without any hint of the offender seeking forgiveness or showing an awareness of their crime or showing contrition. The question is how often is this attitude of offering forgiveness unilaterally and unconditionally to last? Is it a one-off event, something that should be given a good trial (let’s say ‘seven times’) or something that must be on-going (‘seventy-times seven’)? The Christian position is made abundantly clear.

But what is this attitude? The forgiveness in question consists in continuing to seek the way that builds up peace with those who offend one, rather than seeking either to get revenge for their offences or seeking to write them out of the script of one’s own plans for right acting. The Christian must act rightly, despite how others behave, even when that behaviour is directed against them. Reconciliation is the  steady willingness to build the universe aright in spite of, and in the aftermath of, those who would break down peace and goodness between people, or between people and the environment. One must not only seek to stop damage to individuals, society, the environment, but one must always be ready to start over, repair damage, and begin again. This beginning afresh, rather than pursuing a vendetta or engaging in recriminations, is at the heart of reconciliation.

steady willingness to build the universe aright in spite of, and in the aftermath of, those who would break down peace and goodness between people, or between people and the environment. One must not only seek to stop damage to individuals, society, the environment, but one must always be ready to start over, repair damage, and begin again. This beginning afresh, rather than pursuing a vendetta or engaging in recriminations, is at the heart of reconciliation.

3. The task of the Christian body, the church, is to act as an agent for reconciliation in a human situation where, after any offence has been felt, our instincts and’ gut reaction‘ is to find the culprit, extract redress (sometimes we are honest and openly call this ‘vengeance‘ and admit that we like the idea of ‘getting our own back’; sometimes we opt for spin and speak of ‘restoring the status quo’ or of ‘condign justice’), and then have an extended period during which the offender suffers the effects of their crime whether this is imprisonment, isolation, being given the cold shoulder, or some other kind of exclusion. However, reconciliation is focused not upon redress, but upon getting back on track, repairing the damage, and starting afresh. The past is past; we must get on with building the kingdom of justice, love, and peace. If we look back it is only to learn lessons, not to engage in the activity of retribution. This is a very different view of the way humans should act to that which most societies have pursued either now or in the past.

The church is the minister of reconciliation whose vocation it is to work to repair the damage done within the creation, material and human, from evil choices. And this ministry cannot be confused with wagging fingers at problems nor naming sins, nor should it be reduced to the individual reconciliation of penitents, (viewed in terms of an individual’s relationship with God). This working for reconciliation is part of the priesthood of the whole people of God.

The church is the minister of reconciliation whose vocation it is to work to repair the damage done within the creation, material and human, from evil choices. And this ministry cannot be confused with wagging fingers at problems nor naming sins, nor should it be reduced to the individual reconciliation of penitents, (viewed in terms of an individual’s relationship with God). This working for reconciliation is part of the priesthood of the whole people of God.

Wherever there is division, corruption, suffering or disruption in the order of things, there is a task of reconciliation to be addressed; and Christians make the claim that they are willing to adopt this task as their own. In a world where the pursuit of vengeance keeps conflicts running and multiplies the amount of suffering and misery, Christians are supposed to be taking a different tack.

4. Reconciliation is also a way of understanding the Christ event: God in Jesus was reconciling the world to himself. The pattern for all Christian reconciliation is the way the Father has offered a new beginning to the creation in the Last Adam. This use of reconciliation as an overarching theme for the whole of the gospel is captured in the opening statement of the current formula of sacramental absolution: ‘God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins. The Father allows us to begin afresh and to then grow to the fullness of life; we rejoice in this as the joy of faith. We must allow those who have harmed us/ our creation to start afresh and help them grow to the fullness of life; we accept this as the challenge of the life of faith.

4. Reconciliation is also a way of understanding the Christ event: God in Jesus was reconciling the world to himself. The pattern for all Christian reconciliation is the way the Father has offered a new beginning to the creation in the Last Adam. This use of reconciliation as an overarching theme for the whole of the gospel is captured in the opening statement of the current formula of sacramental absolution: ‘God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins. The Father allows us to begin afresh and to then grow to the fullness of life; we rejoice in this as the joy of faith. We must allow those who have harmed us/ our creation to start afresh and help them grow to the fullness of life; we accept this as the challenge of the life of faith.

5. Perhaps we are now in a better position to appreciate the wisdom of Ben Sira: the homily could conclude by reading the first reading again as its various messages (e.g. ‘stop hating’) should now fit into a larger framework.

****************************************************************

John Litteton

Journeying through the Year of Matthew

www.Columba.ie

Gospel Reflection

Why was Jesus so insistent about the practice of forgiveness in the lives of his disciples? Peter was probably embarrassed by Jesus’ answer to his question ‘How often must I forgive?’ Jesus told Peter to be far more forgiving than he was suggesting. Peter must forgive seventy-seven times, not seven times.

In saying this, Jesus was not implying that forgiveness could be refused on the seventy-eighth and subsequent occasions. For Jesus, there could be no limit to the number of times people would forgive. Forgiveness was to be a continuous activity and one of the central characteristics of the Christian lifestyle.

So why was Jesus so adamant that his listeners would understand how his message of forgiveness was central to his teaching and preaching? Was it because he wanted to be excessively demanding? Or was it because he knew that forgiveness was among the most difficult challenges for human beings?

Orthodox priests pray as they stand between pro-EU protesters and police lines in central Kyiv, Jan. 24, 2014.

It would have been easier for most of Jesus’ disciples to be unforgiving because they had direct experience of oppression and injustice from the Romans, who were occupying their country, and from the tax collectors, moneylenders and religious leaders. Did Jesus want to raise the standards and expectation beyond their capabilities? The answer to these questions is an emphatic ‘No’.

Jesus was uncompromising about the centrality of forgiveness because he understood human nature completely. He knew that if people would not forgive one another, and if they could not graciously accept forgiveness from other people when it was offered, then they would be unable to experience God’s forgiveness. Jesus appreciated that the human spirit yearns for acceptance, sympathy, respect, companionship and a sense of belonging. None of these is possible in the absence of forgiveness.

Practising forgiveness, therefore, enables us to realise these yearnings. Our greatest gift from God — the ability to love — is dependent on our ability to forgive. Forgiveness brings healing. If there is no forgiveness in our lives, then our human nature becomes flawed. We feel isolated. We become less than human and, eventually, our dignity and sense of self-worth diminish. Our innate beauty derived from being made in the image and likeness of God is shattered. There is a diminution of the quality of human life and living.

Jesus always forgives

When, as repentant people, we celebrate the sacrament of reconciliation properly (that is, we confess our sins, make reparation for our wrongdoing and resolve not to commit these sins again) we are assured that our sins are forgiven and that we will have God’s help to avoid sin in the future. We all need to experience forgiveness in our lives. The sacrament of reconciliation enables us to receive God’s forgiveness for our sins. We become whole human beings again, capable of tremendous love and sacrifice. Is it any wonder, then, that Jesus insisted on forgiveness among his followers?

Meditation

And in his anger the master handed him over to the torturers till he should pay all his debt. And that is how my heavenly Father will deal with you unless you each forgive your brother from your heart. (Mt 18:34-35)

*************************************************************

Fr Donal Neary, S.J

Gospel Reflections for the Year of Matthew

www.messenger.ie/bookshop

Forgiveness

We are called to forgive; and that can be really difficult. You have been defrauded by the banks of your life’s savings – can you forgive? You were abused as a child – can you forgive? You were done out of a job because another lied to get it – can you forgive? The answer is maybe ‘no’. What then does God want? He asks us to open our hearts to the other so that we may forgive. Forgiveness is the deepest of God’s desires on our behalf, and he hopes that we can forgive each other.

Our hurts and burdens are heavy to carry through life. To forgive can release some of that weight. The person who hurt us may be dead, or may not even know (or care) that we are hurting. When we desire to forgive but don’t know how, one way of looking for this strength is to pray for it. We often pray, ‘Lord, make my heart like yours’. When we pray that we are praying to be forgiving people!

Our hurts and burdens are heavy to carry through life. To forgive can release some of that weight. The person who hurt us may be dead, or may not even know (or care) that we are hurting. When we desire to forgive but don’t know how, one way of looking for this strength is to pray for it. We often pray, ‘Lord, make my heart like yours’. When we pray that we are praying to be forgiving people!

Another way is to pray for the person. When we realise that as God loves me, he also loves everyone, we may find a spark or light of forgiveness in our souls. Out of this we may find the will to meet the other and talk to him or her, and find the grace of forgiveness between us.

Forgiveness sometimes comes slowly. When God sees us wanting to be on the road to forgiveness, he gives us the graces we need to unburden ourselves and be able to love like him.

Sit in silence for a while, and send a blessing or prayer

to someone you need to forgive.

Lord, I ask – make my heart like yours.

********************************